Until I inherited my grandmother’s recipe box, I thought of her place as the hair salon, not the kitchen.

My grandmother was not a cook. Poor and divorced with two children and no English, she immigrated to post-World War II Pittsburgh, PA from Mexico City. To get my mother and uncle through school, she worked in the service industry. Eight hours a day at Pittsburgh’s department store, Kaufmann’s, and a few extra hours at night in her basement or kitchen, on weekdays and weekends, she glided polish with precision over her clients’ nails and dexterously wrapped their hair in rollers. Still, she had what in Mexico, we call sazón, an intuitive sense of flavor that made the tacos she concocted with American ingredients and her oatmeal cookies delectable.

While she worked, my mother and uncle were the homemakers, cooking dinner after school for each other and my grandmother. Out of necessity, they both became excellent cooks, and passed down their love of food—and sharing food—to the third generation.

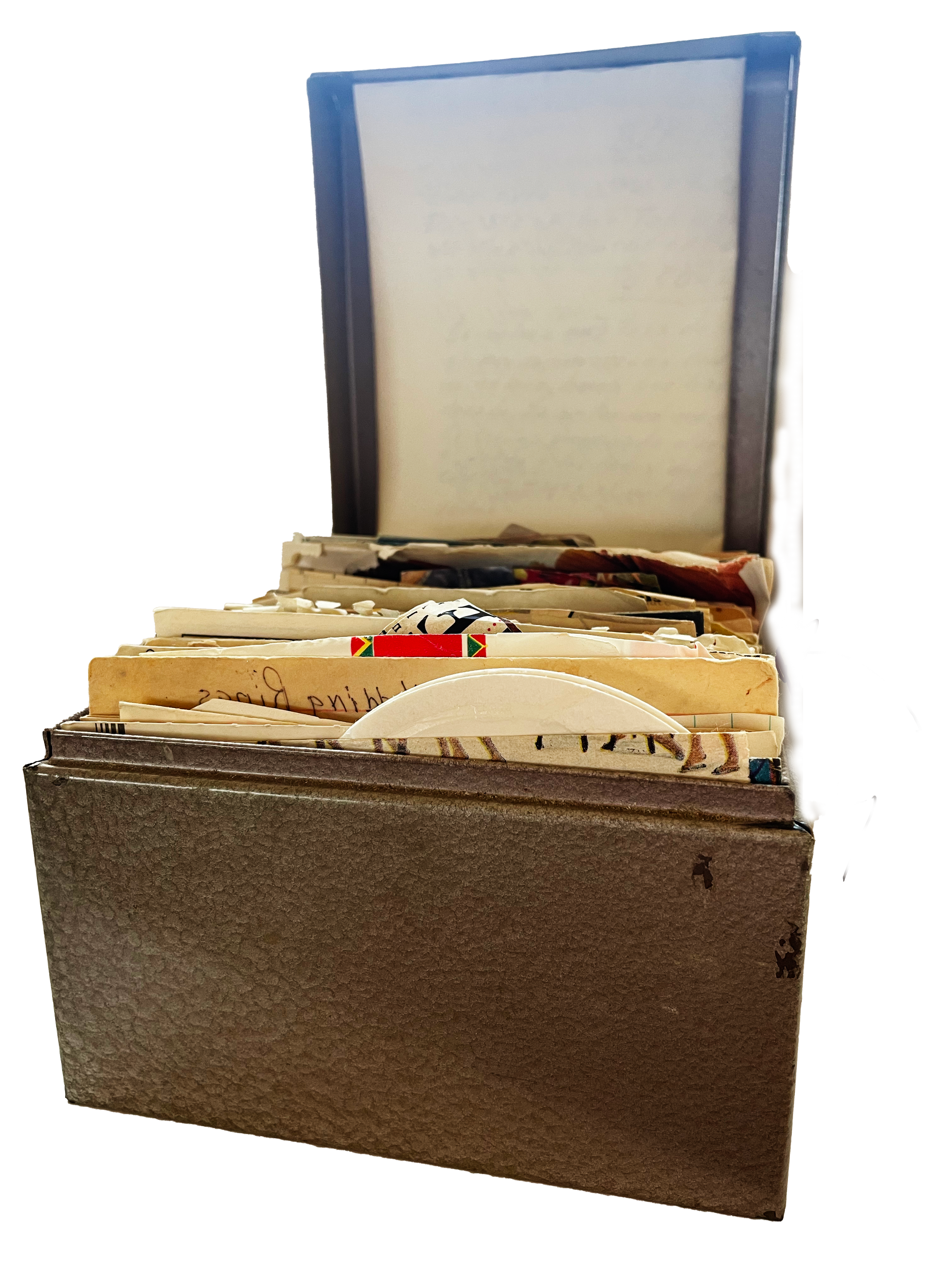

Yet, after my grandmother’s death, when her children and grandchildren looked over the objects that were left behind, nobody claimed the heavy, unremarkable, squared box stuffed tightly with recipes.

I did. I took the box and a pair of rusted thinning shears.

My reflex to take the box was borne of the desperation that accompanies grief and turns objects into extensions of the departed. It was also the reflex of a scholar. I knew that the recipe has been widely recognized as a rich textual genre that documents the history of women across time and space, and I wanted to see what the box would reveal about my grandmother’s own history.

As I sifted through newspaper, magazine, and food packaging cut-outs, as well as handwritten recipes collected from the 1960s to the early 2000s, I gradually realized this box is the material expression of her efforts to incorporate the practices of American womanhood to her way of living. With each recipe, she made a choice: to keep some of the flavors she grew up with and let others go; to adopt Italian-American traditions; to be blissfully domestic while working around the clock. Curated by a working woman who rarely had time to be a cook, it holds her wish for the material conditions that would allow her to be an American homemaker. By extension, it holds the hopes she had for my mother and me, hopes from which we diverged even as we tried to fulfill them. Our own relationships to food and cooking, education, work, marriage, home, are responses to her ruthless independence and how it coexisted with conventional domesticity and her conservative values.

Through seven essays, each based on a recipe, in The Recipe Box: Lost and Found in the Bicultural Kitchen, I unfold a two-way story. In one inward looking direction, the recipe box and its contents are an expression of deeply personal self-fashioning, of inherited and adoptive traditions, of how my grandmother’s choices and aspirations reverberated through the second and third generations. In the other, outward looking direction, the recipe box and its contents are a record of the specific sociocultural, economic, and political forces that shape our taste, material means, and sense of what was and is possible living between Mexico and the USA.

I am grateful for the support of the Tacoma Artists Initiative Program (TAIP) 2025-2026 grant, funded by the City of Tacoma and the Arts Commission.